The sea stretches out in front of Alden McLaughlin, walling him in on his island and beckoning him with waves from the furthest points of the world. The fifth-generation Caymanian knows better than most how far his country has come, and in his second term as Premier, few others know how far it has to go.

For Mr. McLaughlin, an avid cyclist and passionate farmer, there is no greater pressure than the internal expectations of his people. Cayman enjoys the highest standard of living of any Caribbean nation, but its citizens are hungry both for progress and also a lasting marriage to their traditions and culture.

For Mr. McLaughlin, an avid cyclist and passionate farmer, there is no greater pressure than the internal expectations of his people. Cayman enjoys the highest standard of living of any Caribbean nation, but its citizens are hungry both for progress and also a lasting marriage to their traditions and culture.

Those two impulses, sometimes contradictory and mutually exclusive, embody the task that lays before Mr. McLaughlin and his cabinet. The head of government recently took a week off to decompress at a rental home in Rum Point following the initial post-election flurry of activity, and as he greeted a visitor, he mused on what his slate of responsibilities must look like to an uninitiated observer.

“When you’re here for a while, you stand on the outside and think, ‘It’s a little place with 63,000 people. What could be so complicated?’ Then you’re here a little longer and you understand it isn’t just 63,000 people who are farming or fishing for their livelihood,” he said. “We’ve got two major international industries: Financial services and tourism. Plus some other burgeoning things like international healthcare. Then you add the other dimension of managing 130 different nationalities and all the ethnic and other issues that are part and parcel of immigration along with the local issues and concerns and resentments. You come to realize that you’ve got all of the issues of any major, developed country, except in Cayman, they’re seen through a magnifying glass because everybody knows everybody.”

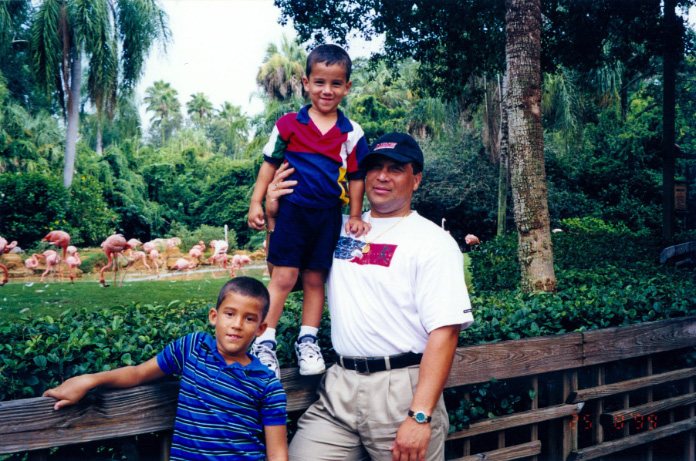

Mr. McLaughlin, father to sons Daegan (25 years old) and Caelan (22), has long been under that magnifying glass, and he helped pen the nation’s new Constitution in 2009. That document, which updated the nation’s governing laws dating to 1972, imposed term limits on the premier, which basically means that Mr. McLaughlin will have no choice but to vacate his office after the next election cycle.

“I was certainly a strong advocate for term limits on the premier. I think it’s one of the wisest decisions I’ve ever made,” he said. “I’m delighted it affects me. I really don’t think that if you do the job properly, you can continue with the level of engagement and effort that is required for more than two terms.”

Mr. McLaughlin can run again for the legislative assembly if he wants to, but someday, he hopes to retire to his farm in East End. The 55-year-old has served the public for nearly two decades, and everywhere he goes, he has a pressing issue brought to him by long-term friends and acquaintances.

“As a representative, you’re so accessible to everyone,” he said. “There is no respite when you’re in this job. There’s nowhere to run and there’s nowhere to hide. If you go to a restaurant or to a bar or a supermarket, there’s someone who wants to speak to you about their issues and their concerns. As the premier, it’s like, ‘I need to talk to you. I know this might not be the time and place, but I never see you elsewhere.’ And that’s the story of my life. But it’s not just me. All the representatives are like that.”

—

It took a kidnapping and a shipwreck to land the first of the McLaughlins in Cayman.

Alden McLaughlin believes that his relatives on his mother’s side – the Boddens – have been in Cayman since before the 1802 census, but he’s learned much of what he knows about his father’s lineage from chats with his grandfather and through a letter passed down from a relative – Captain Stanton McLaughlin – who settled in Trinidad and recounted the family’s humble beginnings in Cayman.

That’s why, with his father who just passed his 91st birthday, he encourages his children to savor the time they have left with their grandpa and to digest every single drop of wisdom that comes from his mouth.

Back Left: Denby Groves (father-in-law), Debbie McLaughlin (sister), Kim McLaughlin, Daegan McLaughlin, Dr. Elizabeth McLaughlin (sister), Alden McLaughlin and Caelan McLaughlin.

Front Row: Marie Groves (mother-in-law), Althea McLaughlin (mom) and McNee McLaughlin (dad).

“One of the things I keep telling my sons, my nephews and niece is, ‘Listen to the old man.’ When my grandfather – his father – was alive, I was very close to him,” he said. “I still miss him. He lived to be 95 and three months. I tell the kids, ‘Listen to him. He tells you the same thing over and over, but there will be some nugget in there that as you get older, you will cherish.’ My grandfather used to tell me over and over – and I’d think, ‘Oh God, not again,’ – about the family lineage. Now I have it in my head.”

The way the story was told to him, Mr. McLaughlin said that his earliest ancestor in Cayman, John Patrick McLaughlin, was dragooned onto a sailing vessel from his home in the Irish port town of Youghal. He was forced into a sailing life, and then, thousands of miles from home, his ship ran aground off Cuba. The boat’s sailors, luckily, were rescued by a Cayman schooner and brought back to Grand Cayman.

This would’ve happened shortly after the turn of the 19th century, said Mr. McLaughlin, and the 1802 census of Grand Cayman does not show a John Patrick McLaughlin among the island’s inhabitants. The story takes a twist shortly thereafter, and it’s something Alden has spent many idle moments pondering.

“One of the most remarkable parts of that story, to me, is that the captain and crew were brought to Cayman, which, at that point, would’ve been little more than a mosquito-ridden backwater with only the most basic, primitive conditions,” he says of life in 19th-century Cayman. “I’ve tried to imagine what the conditions must’ve been, and this was not someone who grew up here. This is a white Irishman.”

Cayman, according to the 1802 census, had just 933 people, and more than half were slaves. Cayman was exporting turtle and cotton, but many of its inhabitants were living a hard-scrabble life.

The captain of the vessel, enjoying the privilege of rank, had his wife on board the boat, and shortly after reaching Cayman, he fell ill and passed away.

John Patrick McLaughlin wound up courting the young widow, and after winning her hand, the pair went to get married in Lucea, Jamaica, because there was no marriage officer available on Grand Cayman.

“Now all that makes sense. Perfectly logical,” said Mr. McLaughlin of his family’s backstory. “The bit I have thought about ever since I learned of the story is, ‘Why did they come back?’

“Jamaica in the early 1800s was a really happening place. This was a remote and entirely undeveloped island that ships called at for water and for turtle. Nothing else. Why would these young people – when this was just as far away as the moon from where they came from – come back?”

The McLaughlins, generation by generation, matured and prospered just as Cayman did around them. Alden McLaughlin’s great-grandfather, Gilbert Magdaly McLaughlin, made a small fortune by cutting and shipping mahogany from the Bay Islands in Honduras – which were then a British possession – to the United States, and he parlayed his hard-earned wealth into acquiring East End land in Cayman.

Alden’s grandfather, William Allen McLaughlin, taught school in Bodden Town and later opened a school in East End before embarking on a career as an attorney and a vestryman. William Allen McLaughlin, born in 1895, was a member of the first executive council – a forerunner to the modern cabinet – under Cayman’s first Constitution, penned in 1959, and he served in politics for four decades.

“We were a dependency of Jamaica when Jamaica was a dependency of Britain,” said Mr. McLaughlin of the old days. “I always tell people we had the lowest form of constitutional status known to the Westminster system of government. We were a dependent of a dependency, and treated as such.”

Alden’s father, McNee McLaughlin, was born in 1926 and worked in a number of roles. He taught in a school on Cayman Brac, then taught in West Bay before going to sea for 10 years. McNee McLaughlin came back to Cayman in 1955 and got married, and he was determined not to go back to sea. He worked as a hired driver and then as a plumber before winning a scholarship to the West Indies School of Public Health in Jamaica, where he completed a three-year course in just one year.

He came back to Cayman again as the island’s first formally trained public health officer in 1959, and then two years later, his son Alden McLaughlin was born. For years, said Alden, his father would preach to him the importance of education and falling in love with the pursuit of knowledge.

“My generation was the first generation that had the opportunity on any scale to get tertiary education. Prior to that, it was only wealthy families, and there weren’t many,” said Mr. McLaughlin of the life his father led. “My father talked about the lost educational opportunities for a whole generation. Their parents were complicit in the exercise of sending these underage boys off to sea. They became then a bread-winner instead of a bread-eater at home. If they were big enough, they’d be gone at 16. And everybody, including the authorities, would help them lie about their ages so they could go.”

Alden’s mother, Althea McLaughlin, also led an atypical life. She received formal training in Jamaica as a dispenser and later worked for the government. Alden’s mother pushed him hard toward an education, and she passed down her work ethic to her son and daughters Debbie and Elizabeth.

“My mother was somewhat of a standard-bearer for women in Cayman,” he said. “When we were growing up, most mothers stayed at home and reared their children. My mother was the subject of considerable censure in the community because she left her children alone. She taught us a whole lot of independence and reliance, and she always joked, ‘My children haven’t turned out too badly.’”

In addition to the premier, Althea McLaughlin raised his sisters Debbie McLaughlin, who is the director of Cayman Prep and High School, and Dr. Elizabeth McLaughlin, clinical head of accident and emergency at the Health Services Authority.

There were just over 8,500 people in Cayman at the 1960 census, and opportunities began to flower for the younger generation. Mr. McLaughlin said he can remember electricity coming to East End for the first time during his childhood, and he can recall so many people who were touched by the work of his grandfather.

“It would really warm my heart,” he said, recalling his childhood. “Anywhere I went as a young man, people would say to me, ‘Who you fa anyhow?’ I would tell them and they’d say, ‘Oh, you’re Teacher Mac’s grandson.’ So many of them would tell me about his efforts to educate them.”

—

Despite a grandfather and a maternal uncle – George Haig Bodden – who were involved in politics, young Alden’s path was far from certain. In fact, he almost resisted the path of higher education.

Mr. McLaughlin, a capable but not internally motivated student, said he got his first real job in the summer before he turned 17, while he was awaiting the results of his qualifying exams for university.

That job – refueling planes at the airport for Texaco – paid him the sum of $350 a month, which was an inconceivable wage for him at the time. The money, combined with the responsibility thrust on him at an early age, had Alden McLaughlin ready to quit school and enter the working world for good.

“I had never seen $350 in my life,” he said. “The first month, I’ll never forget. I had lusted over this stereo at Stereo City. I was a great lover of music and still am, and this stereo cost $356.50. They paid us cash. I don’t remember where I got the $6.50, but I went straight there and paid them the entire month’s check on a stereo. That stereo must’ve been at my mother’s house for the next 20 years.”

Mr. McLaughlin, who had amazed his father by beginning to read at age four, had now decided he’d had enough of academic rigor. He’d made up his mind that he would continue working for Texaco for the next few years, but his father was equally determined to see him avail himself of better opportunities.

“I have my father more than anyone else to thank,” he said. “I don’t remember how it came about, but I told him I was going to stay with Texaco. He was so upset. He sat down and he reasoned with me, argued with me, over many weeks. I said, ‘No, Dad, I don’t want to go back to school again. I’ve had enough of that.’ Up until that point, I’d only seen him cry once, when his mother died in August of 1970. The man broke down. I didn’t know what to do. But I was very stubborn, a trait I’d inherited from him.”

But to understand the argument, you’d have to understand the era. Jobs, so desperate and rare a commodity a generation before, were now readily available to younger Caymanians. Mr. McLaughlin took the opportunities presented to him for granted, and his father was determined not to let him.

“He used to tell me, ‘My boy, you cannot see it yet, but take it from me: The day is coming in Cayman when you’re going to need a degree to drive a garbage truck,’” said Mr. McLaughlin. “That’s why he was so adamant. And you know what he did? I don’t think it would work with this generation of kids, but then we had so much respect and regard and fear for our teachers. He called the principal of the school – it was then Cayman Islands High School, but now they call it John Gray – whose name was Michael Mynett, a little Englishman. Small in stature but we had huge regard for him.”

Mr. McLaughlin was one of more than 1,000 kids at the school, so he never expected a phone call at home from the principal. But one came from Mr. Mynett, inquiring whether he’d be coming back to school, and upon hearing a negative response, requesting a meeting in his office the very next day.

“I had to call my employer, make arrangements,” said Mr. McLaughlin. “My father took off time to cart me there. When Mr. Mynett was through with me, I had agreed to go back to school. Me being me, I had to broker a deal. And the deal with Mr. Mynett and my father was that I would get to keep my job.”

Now, at the age of 17, Mr. McLaughlin was doing double duty. He’d get out of school at 3 or 4 p.m., go home and do his homework, and then work the night shift at the airport from 6 to 10 p.m. He was refueling planes by himself, a major undertaking for a youngster, deep into the evening.

Once set on the path to higher education, his life began to take conventional shape. He left the job with Texaco to take a government job, and soon thereafter, he wound up as deputy clerk of the court.

Mr. McLaughlin would then run into one of the great influences of his life, Ms. Ena B. Allen, the first female Supreme Court Justice of Jamaica who later became Clerk of the Court and Registrar of the Grand Court and Court of Appeal in Cayman. Ms. Allen took Mr. McLaughlin under her wing and began pushing him to enroll in law school, but he still wasn’t ready to make that kind of scholarly commitment.

“She’s dead and gone, but I shall forever be grateful to her. Were it not for her, my life would’ve ended up very differently,” said Mr. McLaughlin of Ms. Allen, who passed away in 2005. “She kept pushing me, but the course was five years long and that seemed like an eternity to me. …I felt like I’d been in school my whole life. For me to go back in shackles for five years seemed like forever.”

Every day, he said, he’d be nudged by Ms. Allen and by Peter Rowe, the first director of legal studies at the law school, to further his education. Mr. McLaughlin, seeking a compromise, decided to enroll in a three-month course in public administration in Barbados, but Ms. Allen rejected his request.

“I went in and said, ‘Mrs. Allen, how can you turn this down? This will be good for me,” said Mr. McLaughlin. “And she said, ‘You, young man, are going to law school.’ I had visions of me and three months in Barbados, unescorted. What fun I’m going to have. But she had the longer view.”

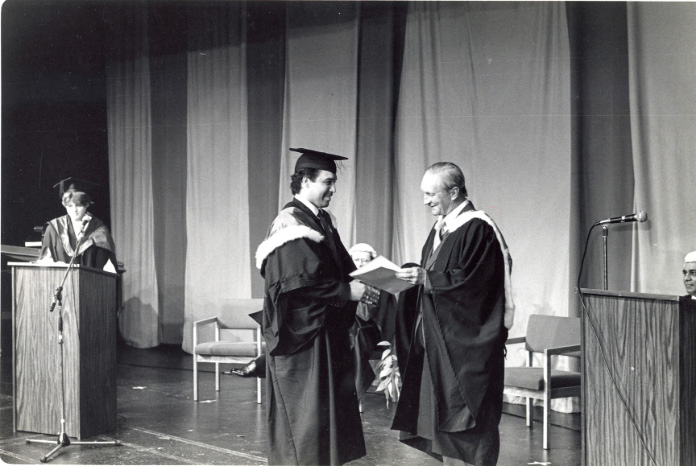

Ms. Allen’s encouragement would pay off for Mr. McLaughlin, who joined the firm of Charles Adams and Co. as an articled clerk in 1984 and would go on to a distinguished law career that lasted more than two decades. He was named partner at Charles Adams, Ritchie and Duckworth in 1993 and would stay at the firm until March of 2006, when he fully committed himself to his life in politics.

Mr. McLaughlin, who was called to the bar in 1988, recently got a reminder of his life in law when elder son Daegan experienced his own bar call. There, in the courtroom, Judge Charles Quin recalled Alden McLaughlin as a young man, a lawyer who would go on to do great things in his profession and out of it.

“Your father doesn’t need any introduction,” said Mr. Quin to young Daegan, who is embarking on a career with Maples & Calder. “I think everybody knows he’s now the premier going into his second term, but before that, what people might not know, is that he was a partner at Charles Adams, Ritchie and Duckworth for many years. And before that, he started life just like you, as a young attorney with Charles Adams and Co. with his mentor Charles Adams and Queen’s Counsel Graham Ritchie. Sadly, that’s quite a long time ago, but it’s a very special day when you’re following in your father’s footsteps.”

Mr. McLaughlin, who married his wife Kim in 1985 as a 24-year-old, would go on to become president of the Cayman Islands Bar Association in 1998. Just two years later, he ran for the Legislative Assembly for the first time.

After winning, he saw the limitations of the government and the fragility of ruling coalitions for the first time. Running alongside Kurt Tibbetts, the future leader of the People’s Progressive Movement, Mr. McLaughlin experienced what it means to hold power and not be able to hold consensus.

“The first group that [Kurt] put together fell apart before we were even sworn in. The second group lasted exactly one year,” he said. “I don’t care whether you call it a party or a movement, but there has to be an organization and structure and a core set of values, principles and policies around which a group of people can coalesce. That doesn’t mean people can’t have different views about things.”

Seventeen years after his first run, Mr. McLaughlin got a chance to draw on that early lesson in governance. Nine independents won seats in the 19 districts of Cayman’s Legislative Assembly in the May 2017 election, and Mr. McLaughlin did not have the numbers to guarantee a ruling coalition.

Still, later that week, the seven members of the Progressives came to a mutually beneficial agreement with the three members of the rival Cayman Democratic Party.

On Friday afternoon, May 26, there was Mr. McLaughlin sitting beside McKeeva Bush, the leader of the CDP, in naming a government cobbled together between the two parties. Hours later, Mr. Bush backed out and named a different coalition that would land him as premier and put the Progressives out of power.

Chaos reigned for the next few days, but by Tuesday, Mr. McLaughlin was back atop the government with a coalition that included Mr. Bush as Speaker of the House. The situation was troubling to many in Mr. McLaughlin’s party, but he said it was never really worrying to him.

“I know the players,” he said. “I know what they would and wouldn’t do. I knew full well that Arden McLean and Ezzard Miller would never support McKeeva Bush as premier. I knew McKeeva Bush would never have Arden McLean or Ezzard Miller as part of his cabinet. Once you understand those basic things, you know that’s a horse that just won’t run. My greatest challenge was keeping my team calm.”

—

When he’s not working, you can find Mr. McLaughlin in one of two places: Pedaling furiously astride his bicycle or plotting the future of his orchard in East End. His 23-acre farm is nestled in the incongruously named Great Beach, and he says, “You could not get further from a beach if you tried.”

Currently, the farm has 650 fruit-bearing trees, and he hopes to increase that to 2,000 in the years he has left on Earth. The McLaughlin homestead grows all manner of produce. Mangoes and avocados. Sweetsop and soursop. Naseberry and longan. Red plums, yellow plums and June plums. Jackfruit, papaya and plantains. And best of all, peppers, both Scotch bonnet and Cayman seasoning variety.

Mr. McLaughlin likes to tell people that he “grew up in the bush,” and he speaks pridefully of the way his family’s East End land has developed over generations.

“My great-grandfather had acquired – by Cayman standards – a lot of land,” he said. “Most of it was considered not worth very much because it was so far in the bush there was no vehicular access. The old people, way back where I’m farming now, never raised crops because it was too far to bring them from. Most of them didn’t have a donkey, let alone anything else to transport stuff, so they raised cattle.”

Now, as roads develop and farmers learn better development methods, even the most inaccessible land can yield succulent fruit. There are three full-time workers on his farm, and part-time workers help out at harvest time. His farm does not currently yield a profit, said Mr. McLaughlin, but he’s confident that it will start making money in the near future when local grocery stores begin to be full of local produce.

“One of the great things that’s happened to Cayman in the last 10 to 15 years is that local produce and fresher produce is actually recognized as being better,” he said. “For a long time, there was a stigma against local produce. …Part of it had to do with the quality and I suppose the lack of reliability. Supermarkets need it every week. If a farmer brings a few hundred pounds this week but you don’t see him again for a month, what do they do in the meantime? Cayman is at a point now, no doubt in my mind, where we can supply all the mango for local consumption. The same with avocado, I believe. And if we have a good season, during the cool months, tomato grows very well. We can supply that as well.”

The farm and cycling are Mr. McLaughlin’s twin passions, and he said that both of them bring him peace of mind. He has not been in a good cycling groove since last September, but when he is, it’s nothing for him to go out four or five days a week and to put 200 miles on the odometer.

On a weekday, Mr. McLaughlin might wake up at 4 a.m. and bike for 90 minutes or more, and on a Sunday, he may bike as many as 75-100 miles. He loves to ride the loop from Rum Point around the Queen’s Highway, and he’s made several trips to Cuba to ride from one province to another.

“When I don’t get to do it, it really affects me,” he said of cycling. “Normally, I don’t really have any health issues. I’ll be 56 in September. But when I don’t ride for extended periods of time, aside from putting on a few pounds, I watch my blood pressure [go higher]. I can feel that I’m so tense. I don’t sleep well. I usually have so much on my mind, but when I do a lot of physical activity, even though my mind might want to go on, the body just shuts down. If I’m not exercising regularly, my brain just won’t quit.”

Mr. McLaughlin estimated that he’s been to the United Kingdom 15 times in his capacity as premier, and he was awarded the MBE in 2010 for his role in rewriting Cayman’s Constitution. He’s had the opportunity to meet two prime ministers – David Cameron and Theresa May – but has not met Queen Elizabeth.

He jokes that he’s not sure whether the heads of government in the United Kingdom regard him as a peer, but in the next breath, he’ll tell you that he’s never been intimidated to be in their company.

“Meeting a prime minister like David Cameron or Theresa May is an honor, obviously. It’s a country much bigger than mine,” he said. “But Cayman is a modern, well-regulated and incredibly prosperous place. The fact that we’re just 100 square miles is just geography. The issues we grapple with are just as complex, sometimes more so, given the smallness of the population and the intimacy of the people.”

Three years ago, Mr. McLaughlin made the long trip across the Atlantic Ocean to the United Kingdom and was a special guest on “HARDtalk,” a BBC program that specializes in hard-hitting and in-depth one-on-one interviews with newsworthy personalities in politics and popular culture.

That was a big moment for Cayman and for its premier, because Mr. McLaughlin was sitting in the same seat that had previously been inhabited by South African President Nelson Mandela, American Presidents George W. Bush and Bill Clinton and other heads of state from all around the world.

“For “HARDtalk,”” said Mr. McLaughlin, “I did a tremendous amount of preparation, because I knew they were doing the same in terms of researching the issues they wanted to hammer Cayman on. Once you know where they’re coming from, you just have to prepare. And if I’m prepared, I’m as good as any of them. Furthermore, there’s nobody over there that knows more about my country than I do.”

Mr. McLaughlin’s office in the Government Administration Building is full of pictures of the premier with famous personalities from around the world, and he said it’s always a thrill to represent his country on a global stage. The person he was most thrilled to meet, interestingly, is champion boxer Manny Pacquiao.

Meeting prominent people – and standing on equal footing with them – is just part of his job, and Mr. McLaughlin stresses that the totality of his experience has left him well prepared to be premier. Even when he’s meeting a world leader, he said, he never wants to lose sight of where he came from.

“It’s always exciting and I think you always have a little apprehension,” he said. “In anything important, if you’re not at least a bit apprehensive, then that means you don’t care. People become complacent. There’s a difference between being intimidated and overwhelmed with the stage you’re on versus having a little nerves, which I think are important. If you’re missing those, you don’t care very much.”

The old aphorism is that “No man is an island,” but in this global economy and climate, it also turns out that no island is an island anymore. Cayman wants to hold on to its local culture and traditions, but it also wants to be a place that is appealing both to tourists and to businesses all around the world.

That dichotomy can cause an unhealthy push and pull between extremes, said Mr. McLaughlin, and the result is sometimes a tension and a resentment from the local population that the government is not doing enough to better their lives. Everywhere he goes, he said, he’s reminded of his duty not just to increase the standard of living but also to make sure it’s spread around to the Caymanian people.

“We want them to feel they’re benefitting more, but it would be untrue to say they haven’t benefitted,” he said. “We want them and their children to have greater opportunities for success in Cayman.”

His life – not to mention his life in public office – has been a fitting window to the changing times. When Mr. McLaughlin was about to begin his tertiary education there were just 16,677 people in Cayman.

Twenty years later, the year before he ran for office for the first time, the population had doubled (to 39,025), and now there are more than 60,000 people that call Cayman home. There are very few places that have seen their population quintuple in one lifetime, and for Mr. McLaughlin, that means that there’s an added pressure to make sure that the old Cayman doesn’t burst at the seams.

“While there are aspects of our heritage we must continue to preserve, the only way to truly preserve them is to make them part of the new Cayman,” he said.

“Otherwise, they become relics. They become museum pieces. Culture is constantly evolving, and Cayman culture now is not what Cayman culture was when I was a youngster. Even what we eat in Cayman has changed significantly. Stewed turtle and stewed conch, those are ours; but brown stew chicken, jerk chicken, curry chicken, curry goat? We’ve adopted those. And we’ve adopted those just in the last 30-40 years. When I grew up, nobody except the Jamaicans ate curry. Now, all Caymanians truly believe that curry is a Caymanian dish.”

Much like the world that John Patrick McLaughlin moved into, Cayman is still full of promise and potential, ready to be molded in the image of its people and with an eye on the future. But unlike the island that existed 200 years ago, it has a history and a sturdy foundation to build upon.

For Alden McLaughlin, there’s no longer the mystery of why he or anyone else would stay here. There’s only the question of what this country can become over the future decades and centuries.

“I was not just born here, but I want to die here, too. And when I die, I want to have my bones interred here,” he said. “I jokingly say sometimes, ‘I wish I could come back in 60 years and see what this place is like and see what our people look like.’ I will never say I’ve been all over the world. …But I’ve been to all regions of the world and to many places. I still have not found anywhere that I think is a better, safer, more progressive place to live than these little islands which we are fortunate to call home.”