In the first episode of BBC television drama McMafia, a young Russian fund manager is asked by a shady potential investor how he would facilitate the bribe of a port authority official in India.

His answer, like in many movies and novels of a similar theme, inevitably involves the Cayman Islands.

“We would set up a special purpose vehicle in a low-intervention jurisdiction, like the Caymans. The SPV would lend money to similar funds in the Bahamas, Panama, until it becomes impossible to trace and reaches your friend in Mumbai,” the London-based fund manager responds and adds: “We would structure it so that your name wouldn’t appear on the share register.”

Financial professionals in Cayman will have grimaced in pain watching the scene in the knowledge that this type of transaction is not nearly as straightforward and that the Cayman Islands is anything but “low intervention” when it comes to due diligence in banking transactions.

For starters, each locally based fund, like the fictional one in McMafia, must under Cayman law fill three compliance roles dedicated to the prevention of money laundering and report the names of the officers to the financial regulator, the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority.

Of course, McMafia is just a fictional TV series, inspired by a book of the same title by former Guardian and BBC journalist Misha Glenny. And, as such, the writers are certainly in their right to take some creative license.

However, the lack of accuracy still matters because from January to March 2018, no less than 16 British lawmakers made references to the television drama in their parliamentary debate of how the U.K. should deal with the influx of laundered Russian funds into Britain and the rise of transnational crime since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Labor MP Rupa Huq, for instance, noted in Parliament that Sunday used to be “McMafia night” in her household. “As the plot unfolded, we saw how billions of pounds can be transferred internationally very quickly, at the click of a mouse on a laptop. It also showed corrupt politicians, violent police, counterfeit goods hawked around high streets and all sorts of other things. It was fiction, but there was some factual basis,” she said.

The legislators were tasked with passing a law that would plug any loopholes that criminals could exploit and find new methods of limiting money laundering in the real world. Yet their main source of expert information appears to have been a crime caper.

The perceived “factual basis” and the incorrect assumption that all offshore centers are secrecy havens had serious consequences.

Public beneficial ownership registers

At the end of the debate on May 1, the House of Commons passed a cross-party amendment to the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Bill. The amendment effectively ordered the British Overseas Territories, including the Cayman Islands, to establish public registers of beneficial ownership.

These registers are supposed to reveal to the general public and the media who the owners of companies and other entities in the British territories are. Curiously, the amendment exempted the Crown Dependencies in the English Channel from similar requirements.

The move is problematic, not least because to install public registers, the U.K. parliament is threatening an order in council. This relic from colonial days involves the British government writing and implementing laws in the territories by ignoring the democratic process there. It effectively disenfranchises elected representatives as well as their electorates, who have no voting rights in the U.K. To make matters worse, the U.K. parliament acted in the area of finance, which is explicitly devolved to the territories.

To enable this course of action required some knot-tying legal gymnastics. The U.K. parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee claimed in its report “Moscow’s gold: Russian corruption in the U.K.” that the overseas territories “are important routes through which dirty money enters the U.K.” While the U.K. government would therefore “continue to respect the autonomy and constitutional integrity of the Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies on devolved matters, money laundering is now a matter of national security, and therefore constitutionally under the jurisdiction of the U.K.”

Not only is this claim debatable, critics also argue that the proposed public register will damage the territories economically without increasing transparency and strengthening the fight against money laundering.

First, public registers already exist in the territories and the ownership information contained therein is available to U.K. law enforcement and tax authorities when they are conducting investigations.

In fact, Cayman and other territories had struck a deal with the U.K. government to set up such beneficial ownership registers only two years earlier. As a result, the owners of Cayman companies are not secret, nor is it possible in Cayman to “structure it” so that a name does not appear on the share register, as McMafia suggested.

The reason the information is not made public is that many financial clients have a legitimate need for privacy. They have become accustomed to the idea that relevant authorities will have access to their information but making it available to the public at large, and having it splashed out in the media, is for some a step too far.

The concern is that if Cayman and other territories, like the British Virgin Islands, cannot provide legitimate privacy, financial services clients will simply shift to other centers, which are not under British control, and still meet their privacy needs. The direct consequence of simply opening up the registers in the overseas territories alone would thus be less transparency. And U.K. law enforcement would lose access to critical information that under the existing beneficial ownership registries in the territories is available to them.

It is also conceivable that clients who do not expressly seek privacy would select, given the choice between two identical services, a service provider in a jurisdiction that does not mandate that their client information is put on the Internet.

The danger of this unlevel playing field with public registers accessible in only a handful of jurisdictions is that business would simply be driven away from places like Cayman with severe economic consequences and without any improvement in transparency.

Mandating public registers may also have legal limits. Privacy rights, as protected by Cayman’s constitution are not absolute, but laws or government actions infringing those rights must be proportionate.

The crucial question is whether it is absolutely necessary for the general public to know the beneficial owners of companies, especially when law enforcement and tax authorities already have access to the information.

There is a certain irony that at a time when the European Union, including Britain, is tightening rules to protect the data of its citizens with a General Data Protection Regulation, which came into force in May of this year, it completely disregards privacy rights when it comes to beneficial ownership data.

In any case, the overseas territories have objected strongly to the introduction of public registers and reiterated their position that they will implement them if and when they become a global standard.

Anti-money laundering

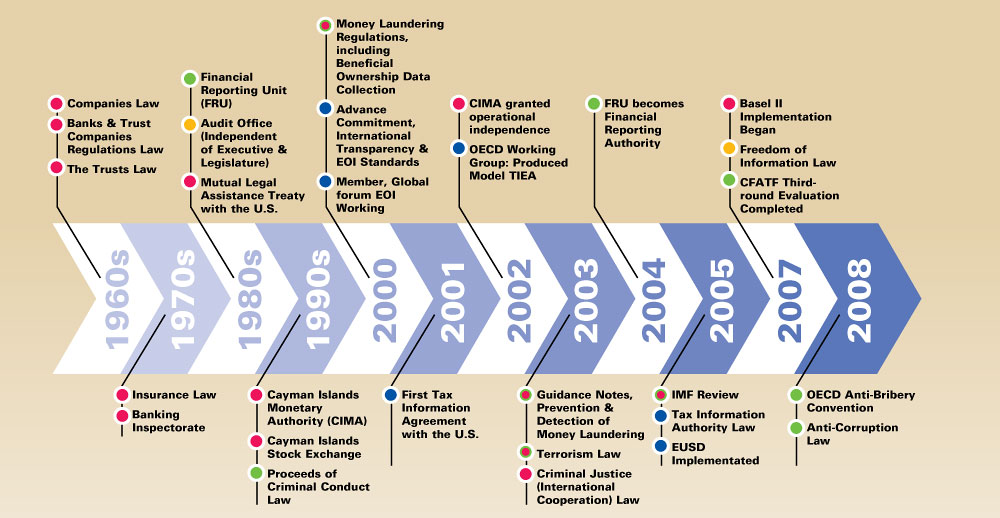

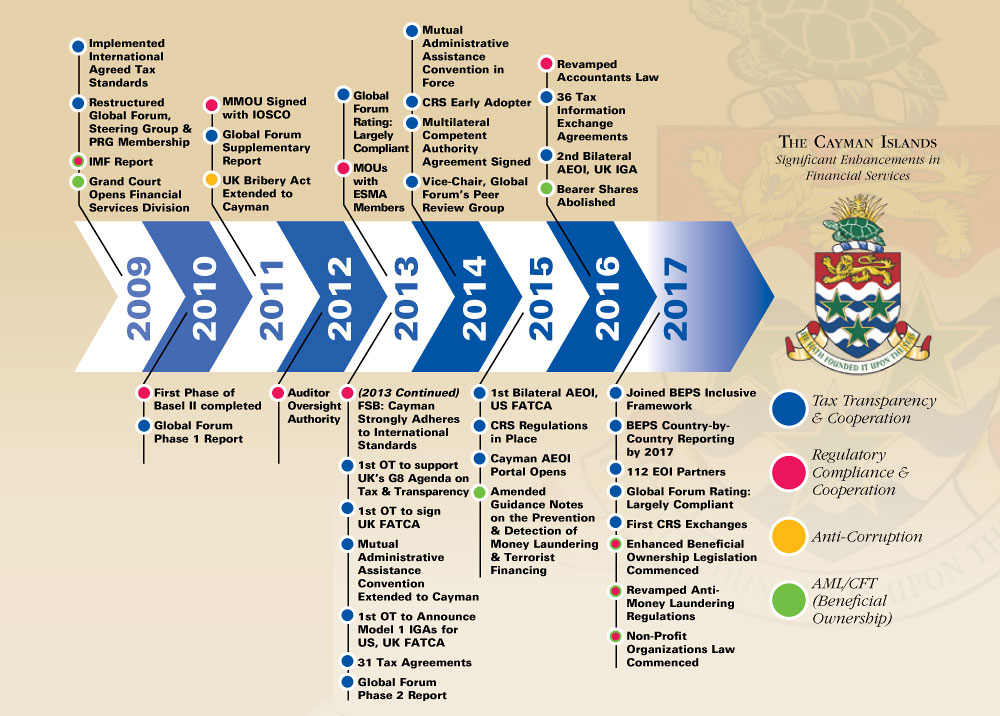

In the meantime, the Cayman government is highlighting the islands’ long track record in keeping its laws and regulations at the forefront of international standards. (See illustration)

This has been acknowledged by standard setting bodies, but the regime receives little attention in the mainstream media.

In 2007, the Caribbean Financial Action Task Force (CFATF) attested the Cayman Islands a healthy compliance culture in terms of anti-money laundering and noted a keen sense of awareness among local financial services providers of the issues surrounding money laundering and terrorist financing.

In a 2009 report, the International Monetary Fund found a legal framework in Cayman that is in line with international standards and a comprehensive system for investigating and prosecuting money laundering and seizing the proceeds of crime.

This assessment is currently being updated after CFATF assessors visited the Cayman Islands last year. In anticipation of the latest evaluation of its AML regime, the Cayman Islands has updated its laws and regulations to continue to be ahead of the evolution of this critical area for an international financial center.

None of this influenced British lawmakers who blamed offshore companies in the overseas territories, in a maelstrom of NGO advocacy and Russian paranoia, for anything from poverty in Africa to Russian kleptocracy and money laundering for organized crime.

Transparency

Just as the perception of Cayman in McMafia belies the actual legislation and practices in preventing money laundering, it is also far from realistic as far as the fight against corruption, international legal cooperation and tax transparency is concerned.

Mentions of the Cayman Islands in Hollywood movies, TV series and novels as a sunny place for shady people and a good place to stash any illicit funds are so commonplace that the phenomenon has become known locally as the “Grisham effect.”

Novelist John Grisham’s legal thriller “The Firm” was not only a literary success, it was turned into a blockbuster movie, shot in Cayman and featuring Tom Cruise and Gene Hackman. The story involves a young lawyer and accountant who starts his career at a Memphis tax law firm that devises front companies for the Mafia to commit money laundering and tax fraud in the Cayman Islands.

Many in Cayman’s financial services industry still argue that book and movie are responsible for many of the misperceptions of the types of business that are done in Cayman.

The reality is much more boring.

Not only is opening a bank account in Cayman today incredibly onerous, when an expatriate has a bank account in Cayman, the account balance is regularly reported to the account holder’s home tax authority. The same applies to other assets, like fund investments and any share ownership in companies and other entities.

Cayman is participating in the U.S. Foreign Account Compliance Act, which forces financial institutions worldwide to disclose the assets of U.S. taxpayers to the IRS. And Cayman is an active member in the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard, which established a tax reporting mechanism between more than 100 countries.

In addition, Cayman exchanges tax information with dozens of other countries on request. An assessment of this type of tax transparency found that Cayman was largely compliant with the criteria developed by the OECD. This puts it on par or above the rating of the U.S., the U.K. or Germany.

None of these findings have influenced Cayman’s media image which is largely shaped by advocacy groups like the Tax Justice Network, whose often-touted Financial Secrecy Index claims Cayman is the third most secret jurisdiction in the world.

One might be right to be skeptical when an interest group releases its own “research,” but a closer look at the index reveals that, even according to the group’s own analysis, Cayman is far from secretive.

Based on the Tax Justice Network’s secrecy score alone, which combines the results from 20 transparency indicators, Cayman would rank 39th out of 112 countries.

It only ends up in third place because the Tax Justice Network decided to weight this score based on the global share of a country’s financial sector.

Vanuatu, the most “secret” jurisdiction, according to the secrecy score, but with few financial services to speak of, ranks 66th on the secrecy list, once this sleight of hand is employed.

Cayman on the other hand, which as the group’s evaluation shows can hardly be called a secrecy jurisdiction, ranks third on the secrecy list because its financial services sector is more successful and globally significant than those of most other countries.